2021

Nick Aikens: “Independent Images: Iris Kensmil’s The New Utopia Begins Here“, 2019

Reviews

Nick Aikens: “Independent Images: Iris Kensmil’s The New Utopia Begins Here“, 2019

Thank you and what a pleasure to be invited here to speak, in front of live bodies, the first time I have done so in a very long time. And what a greater pleasure to do so at the invitation of Iris.

For the next twenty minutes I would like to spend time with, to look at – and to read – ‘The New Utopia Begins here’ with you, Iris contribution to the Dutch Pavilion in 2019 under the title Measurements of Presence’, alongside the work of Remy Jungerman and curated by Benno Tempel. This close reading will, I hope, attend to the highly sophisticated image work that Iris partakes in. It is a form of image work that not only invites us to focus on what and who we see, but equally as significant, how we see.

So – lets go into the Rietveld pavilion. Firstly I want to describe the elements of Iris’ contribution to the pavilion, which consisted of three painted installations.

As you walked into the pavilion and turned to the left a U-shaped alcove housed seven portraits of Black Utopian feminists sitting on top of an abstract composition inspired by the work of Piet Mondriaan and Kazimir Malevich.

Opposite this the work ‘Beyond the Burden of Representation’, comprised of small canvases – painted reproductions of installation photographs of exhibitions by Adrian Piper, Stanley brouwn, David Hammonds amongst others, again sitting within an abstract composition. Included also was a shelf with a number of publications by Black feminist and poret Audrey Lorde, art historians Kobena Mercer and Darby English.

The final wall, which you would encounter on the other side of the pavilion was a wall drawing of Audrey Lorde. Here, as I shall go on to look at, the portrait was applied directly on to the wall with the black rectangular forms sitting within and on top of the portrait.

So – looking at the seven portraits. These portraits show

bell hooks (b. 1952),

The Pan-Africanist Amy Ashwood Garvey (1897 – 1969),

DJ and singer Sister Nancy (b. 1962),

journalist and activist Claudia Jones (1915 – 1964),

communist and activist for Surinamese independence Hermina Huiswoud (1905 – 1998 )

anti-colonial writer and surrealist Suzanne Césaire (1916 – 1966),

and feminist science-fiction novelist Octavia E. Butler (1947 – 2006).

Two of the images are in colour, the other five are just not black and white. They sit on an abstract diagonal composition inspired by a photograph Iris saw of Piet Modriaan’s studio, taken shortly after he died, combined with an appropriated version of Kazimir Malevich’s constructivist lines.

Do we treat these images of Black utopian feminists as prompts to discuss their lives and their ideas? Or are the personalities secondary to the manner in which Kensmil depicts them and installs these portraits on the walls of the gallery: The format of the portrait itself which to some extend defines Iris’ work, the treatment of paint, of light and colour within the works; the fact that these women appear over the reworked abstract forms of Russian constructivism and de Stijl. Or do we simply consider what it means to bring these figures together within the context of the Rietveld pavilion, the spatial embodiment of Dutch modernism and the Venice biennale, the antiquated form of cultural representation based on nationhood? The power of ‘The New Utopia Begins Here’, for me, lies in their claim on the viewer to do multiple forms of aesthetic, intellectual and historic work. It asks us to pay attention to the choices Kensmil makes in who she represents as well as how she organizes and mediates them – what art historian Darby English would call ‘strategic formalism’.

In 1972 Gerhard Richter presented 48 Portraits (1971) in the neoclassical German Pavilion, built at the height of National Socialism in 1938. The portraits were of scientists, politicians and writers: Albert Einstein, Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky, Oscar Wilde, Thomas Mann and Franz Kafka.

Looking at 48 Portraits in relation to Iris’ paintings, one recognises the framing of the portrait to include shoulders, neck and head, as well as the reduced palette and the fuzzy edges of the photorealist aesthetic. While much of the commentary on 48 Portraits selectively ignores the fact that no women or people of colour are included, instead focusing on the formal similarities between the portraits, we should not be blind to Richter’s choices.

In the same vein that Kensmil chose to paint these women in the Dutch national does not mean we should overlook the remarkable aesthetic sophistication of her paintings and installation – but it does mean we should pay due attention to the decisions she took in determining whom we encounter.

If Black feminists have been recurrent presences in Kensmil’s work, from figures such as Gloria Wekker, Philome Essed or Angela Davis, never have they been so deliberately foregrounded as in the Dutch Pavilion.

That Kensmil chose to do so within the Rietveld Pavilion, a building that comes to stand as a form of spatialized modernism, is significant. Griselda Pollock has cogently argued for understanding modernism and its early representations of women as sexualized and gendered, determined by the unequal power relations between men and women.

In her essay ‘Modernity and the Spaces of Femininity’, for example, she points to the depiction of women by male painters as being concomitant with bars (Manet’s A Bar at the Folies-Bergère, 1882) and brothels (Picasso’s Les Demoiselles d’Avignon, 1907). ‘We must inquire’, she says, ‘why the territory of modernism so often is a way of dealigning with masculine sexuality’, before asking straightforwardly: ‘What relation is there between sexuality, modernity and modernism?’

Kensmil’s choice to invite these Black feminists into the Rietveld Pavilion counters both the representations of women in modernist art history and offers a Black feminist approach to art history itself. An art history that, through the presence of these women and, by inference, the ideas espoused, insists on understanding practice as made up of multiple social and cultural conditions. A feminist art history that rejects the singularity, the finality of the single artwork and its male producer. The very presence of Kensmil’s Black Utopian feminists in the Rietveld Pavilion, goes further – it quietly exposes and then explodes the limitations of such outdated thinking.

Perhaps more fundamentally, the inclusion of these women under the guise of ‘The New Utopia Begins Here’ claims the forward, utopian projection of modernism through the lens of Black feminism.

The presence of Octavia E. Butler, whose science-fiction novels from the 1970s onwards can now be seen as foundational for the work of feminists Donna Haraway, Sadie Plant and others, is instructive. Kodwo Eshun, the writer, theorist and member of The Otolith Group, has argued that Butler’s science-fiction writing puts forward the argument of ‘the human or humanity as a revisable project’. In a similar vein, the inclusion of Butler, Jones et al. in the Rietveld Pavilion lays claim to modernism and modernity itself as a revisable project, driven by the presence and ideas of these women that simultaneously embrace science fiction, Pan-Africanism, poetry and music. Set against the composition in black and blue-greys of Kensmil’s wall painting, these faces emerge, re-mixed and re-vamped, as the alternative future which modernity could have had. The brilliance of Kensmil’s gesture is that she makes going back to the future possible.

Returning to Richter – he opted not to include any artists in his selection for fear that he would be perceived as being for (or against) certain artists.

On the wall facing these seven portraits Iris pays homage to the work of artists that have been formative for her work: David Hammonds, Adrian Piper, Stanley brouwn, amongst others as well as including books that have shaped her discursive and political thinking. Art historians Kobena Mercer and Darby English and Black feminist and poet Audrey Lorde …

In a wonderful text on friendship, artist Céline Condorelli suggests that the notion of friendship need not be restricted to a relationship between people, but should also encompass the ideas and politics one holds affinity with; the books we read, the theories that inspire us or the music we listen to. In this sense we can view both the people, Kensmil’s cast of characters, and the ideas they carry with them as Kensmil’s artistic, intellectual and ideological friends. Culture, Hannah Arendt eloquently stated, is ‘the company that one chooses to keep, in the present as well as in the past’.

It IS also worth considering Iris’ relationship to – and mobilizing of discourse within the installation, either through the portraits of intellectuals or the inclusion of publications in her installations. The references these figures and books speak to are highly strategic, placing her work within a wider cultural, theoretical and historical context. They constitute what art historian Griselda Pollock, following cultural theorist Raymond Williams, would call the ‘conditions of practice’ through which we might approach her work: The ideas, politics and people that produce the work. Equally, understood in this way, foregrounding the discursive is a rebuttal to modernism’s deeply held belief in the primacy of the unique art object that should be read in isolation.

Independent Images

Now I want to turn to the forms of image-work at play in Iris’ contribution to Measurements of Presence. Going past the remarkable encounter between Iris’ portraits of the Black Utopian feminists by the abstraction of Mondriaan and Malevich and the light filled spaces of the Rietveld Pavilion – I want to turn to what I think is a more fundamental, yet conceptually sophisticated proposition, that is taking place at the level of the image.

In an interview with Willem de Rooij in the publication for the pavilion Kensmil comments on the relationship between her meticulously constructed paintings and the photographs that are her source material: ‘They need to become independent images’, she says before concluding succinctly: ‘A painting is not a photograph and you can play with those differences’.

Let’s look again at the grouping of seven portraits.

In Iris’ interview with de Rooij she comments on the decision to paint two of the women in full colour.

The choice to depict all but two of the women in almost black and white does not reflect the fact that they were alive before colour photography came into wide circulation.

Rather, Kensmil chose to paint Hermina Huiswoud and in colour to make us aware of the type of images we were looking at, to reference different forms of image reproduction and draw our attention to them as constructed – whereby we acknowledge that it was her choices determined the manner in which we saw them.

Kensmil’s relationship to photography is fascinating. Her use of thinly applied luminous undercoats, which give her subjects such vitality and presence, is a technique first used by the Impressionists such as Manet or Degas – important reference points for Kensmil or, as Pollock draws our attention to, the pioneering work of Mary Cassatt and Berthe Morisot. This exploration of the qualities of paint was happening at a time when painters were grappling with the implications of the invention of photography for their medium. A grappling that would have profound ramifications for the canon of painting through post-impressionism, cubism and of course the geometric abstraction of the constructivists in Russia and de Stijl in the Netherlands.

In this U-shaped gallery, not only do we have an encounter that asks us to re-imagine modernity – via the sampled forms of Malevich and Mondriaan serving as a backdrop to the faces and lives of these future-oriented Black women. Kensmil also lays out in front of us different forms of image making, that take us back through the introduction of photography, and painting’s response to the ‘age of mechanical reproduction’ – both in the form of impressionism’s techniques, as well as the resulting abstraction. She invites different genealogies of images to share space. What is significant of course is that she does this via the images of these women – who have strived in different ways to be foregrounded: either through independence struggles, as Black feminists or through creative work. Women who would not have been known to the vast majority of visitors to the Rietveld pavilion, in contrast to the all too familiar lines and forms of avant-garde abstraction. Kensmil mobilises the formal, material qualities of painting in a highly subjective, constructed process.

Turning to the background. The composition, as I mentioned previously is inspired by a photograph of Mondrian’s studio and composition of Malevich.

Behind these portraits she brings these two together in grey scale as if a DJ would blending two tracks. Iris sampling Mondrian and Malevich on her terms.

In a filmed interview Iris comments on the fact that the seeming geometric composition is, at certain moments unsettled. Right angles, appear subtly off kilter, giving what Kensmil calls its cadence, the composition’s humming dancing vitality. Indeed, standing in the pavilion you could imagine the diagonals and T-shapes sliding past one another, reconfiguring as the portraits of these seven portraits women stay rooted to their spot.

On the wall facing these seven portraits was the work ‘Beyond the Burden of Representation’, consisting of a series of smaller canvases and two wall mounted shelves on which stood a number of publications. The wall can be read as a homage of sorts to artists who have been formative for Iris: stanley brown, Adrian Piper, On Kawara, David Hammonds, Charlotte Posenenske. The miniature canvases are painted reproductions of installation photographs from different exhibitions:

Adrian Piper at MoMA, stanley brown at the Van Abbemuseum. Kensmil’s painted archive of her own art historical canon, the company she chooses to keep ….

Next to them are a selection of books: Audrey Lorde, Kobena Mercer, English’s How to see a work of art in total darkness – writers who have been formative for Kensmil. A second vitrine houses a catalogue of brouwn. The two shelf-vitrines and the small canvases sit on top of a continuation of the Malevich/ Mondriaan composition. The size of the miniatures and the shelves, and the fact that they appear in the same grayscale as the wall drawing means they too become components within the abstract composition, merging with, or dancing amongst the rectangles and flecks of Malevich and Mondriaan, the viewer tasked with discerning what sits within the frame of the canvas and what sits on the wall, what are abstract shapes and what are representations, what images we think we know and what images we need to work to discover.

Kensmil’s exploration of different forms of image making continues with the vast wall drawing of Audrey Lorde. Whereas with the series of seven portraits of the Black Utopian Feminists or the miniatured archive, Kensmil overlaid the canvases or the on to the sliding lines of Malevich and Mondriaan, here she works directly on the wall. The relationship between ‘background’ composition and foregrounded image is inverted. And whereas the painted books of On Kawara echoed the Modriaan-esque geometric blocks so that photograph, painted reproduction, and abstraction became interchangeable, here Lourde’s image applied directly on to the wall of the pavilion rather than contained within a canvas – her image the ground from which Mondriaan’s lines flicker in the foreground.

So here, we have a sense across this three sets of images of foreground and background

changing places, the cast of characters and references in the pavilion being reconfigured.

The wall drawing is also taken form a photograph, yet now the black rectangles that appear on top of the image seem as if the flickering of a television set, or the pixels of LCD screen. It’s not hard to imagine them dancing across the wall before vanishing – leaving Lorde’s image un-interrupted and crystal clear. My reading of this image in relation to TV imaging is speculative – but it’s a reading that is symptomatic of the type of image-work Iris undertakes and in turn invites us to do. We are taken through a topology of paintings’ relationship to mechanically reproduced images and the archive itself. However, in presenting these women, artists and writers within this topology she calls on us to question not only what and who sits in our respective foregrounds and backgrounds – but how we come to see them: forms of representation, abstraction, and the fiction of art history, Kensmil tells us are all constructed. Re-tune your eyes, she seems to say, and a different set of images, a different set of histories, can come into focus.

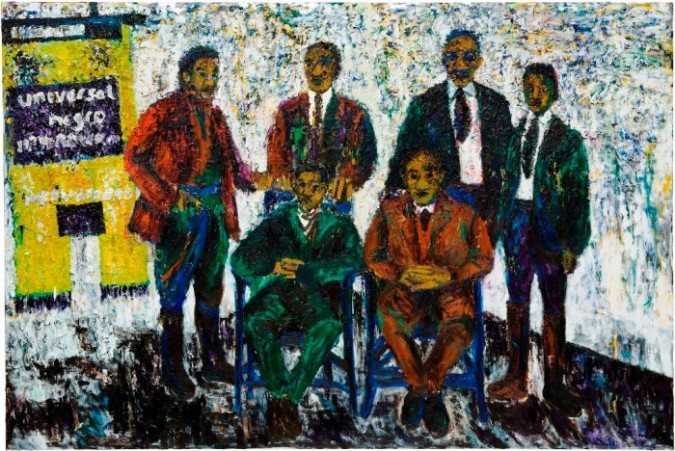

I want to end by considering an image that is not in the pavilion. The painting is titled ‘Archiving a Future History’ from 2017. It shows Jessica de Abreu, co-founder of the Black Archives in Amsterdam (which opened in 2016) and a collaborator of Iris’, holding two photographs. The photographs are of Suriname-born political activist and first Black member of the communist movement Otto Huiswoud and his wife Hermine Huiswoud, who Kensmil would go on to paint for the Dutch pavilion. De Abreu collaborated with Iris on the Dutch pavilion – they decided together on the women that would be represented there, whilst Jessica researched their lives and works, writing entries for each of them in the book. This painting, is also testament to the their collaboration and the manner in which their work facilitates and speaks to one another’s: the images that Jessica’s archiving engenders and visa versa – how Iris’s images bring the archive into being, both as images and through the research that takes place around them.

In this painting Jessica is wearing white gloves and is standing in the centre for research into Black culture in Harlem, New York. The top photograph shows Otto and Hermine at a reception in Cuba, given in their honour after they were re-united following the end of world war two. The bottom image shows Huiswoud at his piano.

Let’s consider what we see here: A painted image, based on a photograph, showing an archivist – the co-founder of the first archive dedicated to Black perspectives in the Netherlands – holding two photographs of the first Black communist and his wife, drawn from an archive of the history of Black struggle. What future history is being called upon in the title – the one that people unfamiliar with the life and politics of Otto Huiswoud will come to know? The history Jessica and the Black Archives will form in their work in the Netherlands? Or the painting itself – as archive, as independent image? This painting draws together Kensmil’s sophisticated image-work where different forms of representation – photographic, painterly, archival and of course political – sit within carefully applied paint. Yet for all its references and evocations, the painting remains an independent image.

Nick Aikens, lecture at De Balie, september 2021